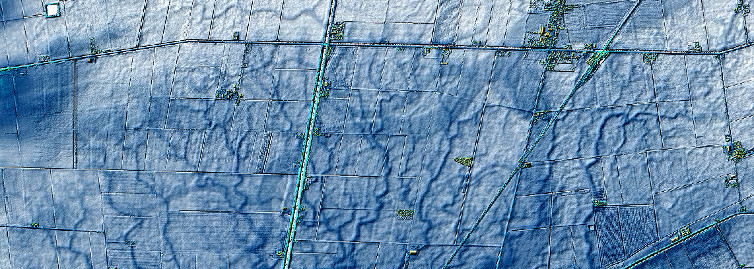

The processed Lincolnshire fenland lidar plot ultimately encompassed some 2250km2 and was always a difficult thing to share (it sits now in various repositories in 5km- and 10km-square blocks). The full resolution 3Gb tif image probably still counts as 'large' in these days of Tb disks (much easier to store, still not very easy to transmit). But finally, through the medium of Leaflet, a zoomable, pannable, map awaits. Just follow the image link above or read on to find out more about the project, the processing involved, and what the colour scales you see actually indicate. The leaflet map loads with a straightforward OpenStreetMap background. Lidar layers can be selected from the menu, with opacity controls below. There are three lidar layers. Fens is the Lincolnshire fenland, the subject of the original project; Marsh is the Lincolnshire Marsh, the rather different, but equally low-lying north-sea coast; Cambs is the southward extension into the Cambridgeshire and Norfolk fenland. All overlap to provide a not-entirely-seamless map (see below) of 5250km2 in total.

Archaeological study of the Fenland has a long history. Too long to revisit here, but key studies would include The Fenland in Roman Times (Phillips 1970) and the eleven Fenland Project volumes published between 1985 and 1996 (now all available online), and not to mention everything about Flag Fen, Must Farm, Stonea, the Car Dyke, and much more. A defining point, recognised from an early date, is the influence of fine topography on the patterns of settlement in these landscapes of very low relief. The Fenland Project mapping made a particular point of including detail of the networks of roddons, the extinct silt-filled creeks which provided firmer ground within the peat fen, mapped then from aerial photography and field survey. The lidar dataset allows these to be extensively and consistently mapped across the whole of the fenland. No other source of mapping comes close to providing this level of topographic detail.

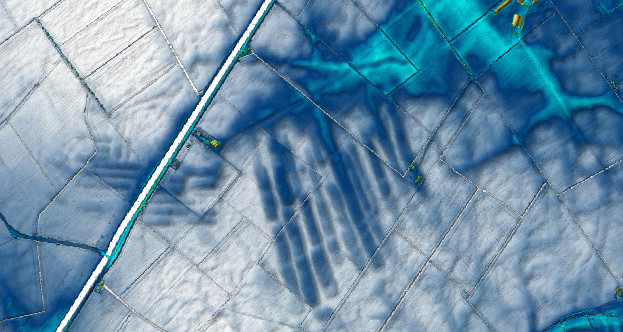

Dendritic pattern of drainage southwards from East Fen overlying earlier watercourses draining eastwards (and here somewhat northwards) towards the (former) coast in the vicinity of Wainfleet.

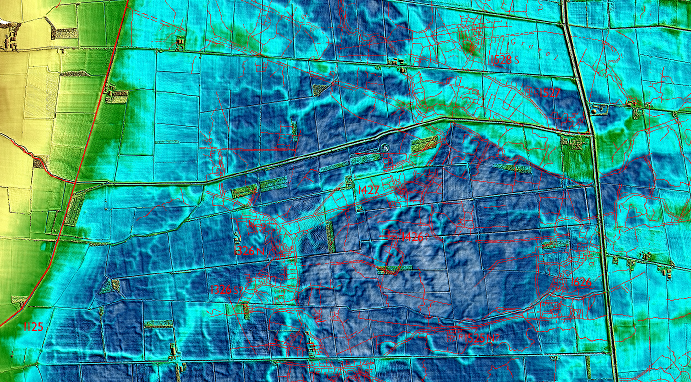

The point, of course, is to see the extensive and detailed cropmark landscapes of the fens against the lidar map, showing how the locations of settlement sites and routes of trackways and watercourses are influenced by this fine-scale topography, revealed in detail for the first time.

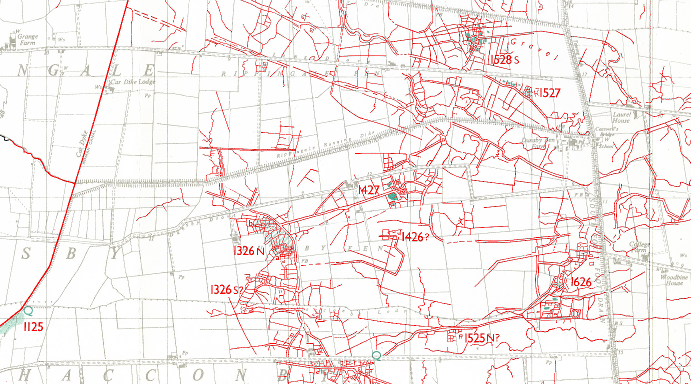

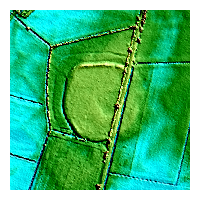

Cropmarks in Rippingale and Dunsby Fen. After The Fenland in Roman Times Map 2 (top); overlain on the lidar topography (bottom).

The genesis of this fenland lidar project lay with the offer of newly captured EA lidar data to the Witham Valley Archaeological Research Committee back in 2005. Its remarkable potential for mapping the fenland landscape was immediately apparent and there began a long process of ever more ambitious data requests (under the much more restrictive licensing regime then in place; the current open data environment makes all the difference). Initial stages were unfunded, which is to say Heritage Lincolnshire/Archaeological Project Services were paying for the bits that didn't happen in my own time. Pulling it all together into a uniform processed dataset which could be shared relied on Historic England funding and resulted in the project reports below (some examples from which are presented here also). Addition of the Lincolnshire Marsh and Cambridgeshire/Norfolk fens was an unfunded and rather piecemeal project undertaken once the data became more freely available. Now that the National Lidar Programme has plugged the remaining gaps, I really ought to revisit this; when I find the time.

The processing style was governed by the essentially topographic aims of the project (to define the landscape setting of archaeological features, rather than necessarily to prospect for the unknown). I probably wouldn't approach it in the same way now (at the very least get a multi-directional hillshade in there), but it still serves its original pupose well. The style is also somewhat platform dependent, created using MapInfo (v7.8 and upgrades to v9.0) which had a rather different approach to production of hill-shades, not exactly reproducible in later versions or on other platforms (which caused me a headache when it came to finally extending into Cambridgeshire and Norfolk). Assembly and export of XYZ tiles has now all been achieved under QGIS.

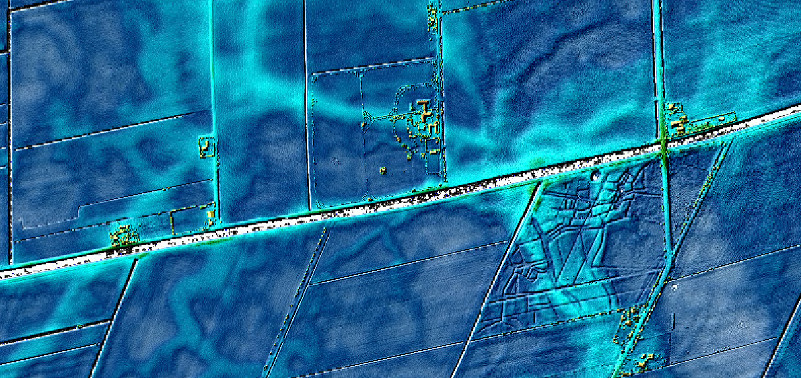

The Car Dyke south of Garwick (north is to the left). The channel and embankments of the Roman canal show clearly along the higher ground at the fen edge.

Processing was undertaken on the 2m-centred Digital Surface Model dataset which then provided the widest coverage. 2m was sufficient to resolve the generally large-scale topographic features and allowed mapping at 1:5000 across the entire area (this is the highest zoom level available in the leaflet map). DSM was preferred since tree cover is hardly an issue in this landscape and it provides better mapping of contemporary settlement (the pattern of which is equally dependent on the underlying topography). The colour ramp was designed to make a sharp distinction at the fen edge, effectively the 3m contour. Land above this shades from green (3m) to yellow (5m) to brown (10m). The white-blue-cyan scale represents everything below, with the lowest values white. The use of a continuous rather than discrete colour scale makes for a less objective plot (where exactly is 3m?) but is much more expressive of the landscape. One unfortunate aspect persists, at least in respect of bringing in Cambridgeshire. In the northern fenland the colour ramp started at sea level, 0m O.D. (excepting some small, self-contained areas that fall slightly below). Much larger parts of the Cambridgeshire fens fall below 0m, some below -2m. This results in a whiting out and loss of detail under the original colour ramp, but resetting the minimum changes the white-blue gradient so I no longer have a completely seamless map. I'm not about to redo the whole of Lincolnshire at this stage (maybe one day), so for now we'll have to live with it.

Turbaries in Upwell Fen. The disused Roman peat cuttings have become infilled with flood silts and now stand out against the background of the drained and deflated peat fen. The morphology is distinctive and these can be widely seen along the route of the Fen Causeway and fringing Marshland Fen.

Earthworks of Roman settlement at Shell Bridge with former canalised watercourses to the west and north. The route can be traced seawards to a possible outfall into the Nene estuary near to Long Sutton.

References

Bennett, R., Welham, K., Hill, R.A. and Ford, A. 2012 'A Comparison of Visualization Techniques for Models Created from Airborne Laser Scanned Data', Archaeol. Prospect. 19, 41–48.

Doneus, M. 2013 'Openness as Visualization Technique for Interpretative Mapping of Airborne Lidar Derived Digital Terrain Models', Remote Sensing 5(12), 6427-6442

Historic England 2018 Using Airborne Lidar in Archaeological Survey: The Light Fantastic, Swindon

Kokalj, Ž. and Somrak, M. 2019 'Why Not a Single Image? Combining Visualizations to Facilitate Fieldwork and On-Screen Mapping', Remote Sensing 11(7), 747.